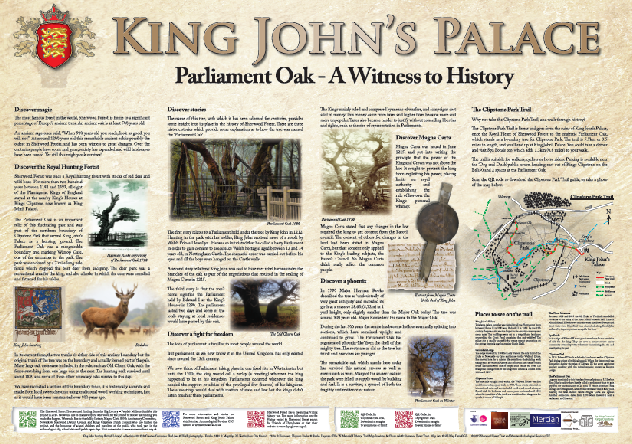

The Palace was visited by all 8 kings from Henry II to Richard II, with King John possibly holding parliament there in the early 13th century and Edward I holding Parliament there in 1290.

Recent Archaeological work -

The palace was sat at the heart of medieval Sherwood Forest and provided amenities for hunting, royal retreat, and the entertaining of foreign royalty and important members of society, with Richard I having once met William the Lion King of Scotland there…

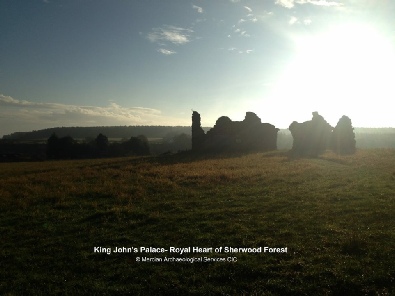

Mercian Archaeological Services CIC via The Sherwood Forest Archaeology Project seek not only to research and understand the site, but to do so with the community, and to raise the profile of the site so that it is once again recognised as the Heart of Medieval Sherwood Forest, around the world!

The Official Research

Community Archaeology Nottinghamshire, Community Archaeology Derbyshire, Community Archaeology Leicestershire, Community Archaeology East Midlands, Mercian Archaeological Services Community Archaeology for Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Sherwood Forest, Leicestershire and the East Midlands. Community Archaeology Nottinghamshire, Community Archaeology East Midlands, Community Archaeology Leicestershire. Archaeological

King John’s Palace and King’s Clipstone

The Sherwood Forest Archaeology project focuses heavily on the site of King John’s Palace (previously known as the King’s Houses) in Clipstone with dozens of projects having taken place there over the last 8 years, and is the official research at the site.

The site is at the heart of the Sherwood Forest Archaeology Project, reflecting the fact that it was once the Royal Heart of Sherwood Forest.

Things to see on the Official Archaeology and History of King John’s Palace web page:

About King John’s Palace-

What do we know about the site? What we do know and what we don’t know about Clipstone, including the most recent findings…

The designed medieval landscape of Clipstone and Arthurian romance:

Discover the designed royal romantic hunting landscape of Clipstone, and the links to the Gawain and the Green Knight poem and the landscape of Clipstone.

List of Archaeological projects at the site:

Who has actually been working on the site of King John’s Palace and what did they find?

2013-

2009 -

1991 -

1956, Earlier Works

Historical Timeline for the medieval Kings Houses at Clipstone:

As part of the Archaeological And Historical background to Clipstone-

Interpretation panels, tours and information leaflets:

View the latest information panels and outreach from around the palace and landscape from the comfort of your armchair.

About King John’s Palace and Clipstone-

Prehistoric to Early Medieval

Evidence of minor prehistoric activity has been found on the site. During excavations in 2012, a flint flake was found. The flake dated to sometime from the Mesolithic to Bronze Age. The flake is not a formal tool and is most likely to be debitage (waste). This suggests that people may have undertaken some form of activity in the vicinity during the prehistoric period. The type of activity is unknown but the presence of this piece of flint suggests it might have included flint knapping (Budge in Gaunt et al 2015).

In 2014 residual finds from excavation by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC included a “few pieces of worked flint from a blade producing industry of probable later Mesolithic or early Neolithic date” (Budge 2014a).

Excavation in 2015 by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC discovered a few knapped flint artefacts. These showed “no obvious concentrations or patterns in their distribution and appear to represent no more than a background scatter, indicating minor prehistoric activity in the area but certainly not suggesting occupation or any kind of intense activity on the site. There were no tools or diagnostic pieces and a general date range of Mesolithic to Bronze Age is likely. Previous archaeological finds of blade-

A Bronze Age spearhead (Nottinghamshire Historic Environment Record, 5965) and an arrowhead (Nottinghamshire Historic Environment Record, 5909) have been found in the parish (Gaunt 2011).

The National Mapping Project data as provided by English Heritage shows a number of cropmarks recorded from aerial photography in the northern quarter of Clipstone parish. Typologically, and from their orientation, it is possible that these are part of the brick-

A test pit excavated by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC towards the highest part of Castle Field yielded a significant number of Pot-

The 2015 excavations by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC also found large quantities of Pot-

A number of Roman coins are listed on the Historic Environment Record for the Clipstone parish (Gaunt 2011). Residual Roman Pottery sherds have been found around Castle Field in various excavations (Rahtz 1960; Wessex 2011; Gaunt et al 2015) including those by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC (Budge 2013; Budge 2014a; Budge 2015; Budge 2016 in press). Excavations in 2014 by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC has extended the dating of Roman occupation by up to a hundred years. These excavations 100m southeast of the standing ruin discovered residual Roman pottery “including the rim of a bead and flange bowl (sensu Darling and Precious 2014) of mid 3rd to 4th century date, extending the known chronology of Roman Activity on the site beyond the second century” (Budge 2014a).

Excavation in 2014 of a linear feature (discovered by Geophysical Survey (Gaunt 2014; 2017)), revealed “a ditch with relatively steep, flaring sides in the upper part of it’s profile narrowing to an almost vertical sided slot towards the base. Aside from a few pot boiler stones its extensively leached main fill was devoid of finds” (Budge 2014a). This ditch cut by an overlying later ditch. A residual sherd of Stamford ware pottery was found in the fill. This sherd “should not post-

Prior to the recent work by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC only a single piece of Saxon pottery representing a “casual find by the landowner” had ever been found in Clipstone.

Budge has recently pointed out that references by other writers (Wright 2016) “to Saxon Pottery found at the palace derive from the the mis-

However recent excavations by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC in Castle Field in 2014, 2015 and 2016 have uncovered large quantities of Saxon pottery covering Early Saxon, Middle Saxon, Late Saxon, and Saxo-

These discoveries are significant in understanding the earlier occupation and uses of the pre-

Domesday Book shows that in 1066 the manor had two owners Osbern and Wulfsi (see below).

The excavations by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC in both the village (Budge and Gaunt 2013), in Castle Field (Budge & Gaunt 2013; Budge 2013; 2014a; 2015; 2016) are beginning to build up a picture of occupation in the Saxon period that was previously unknown.

Medieval

The Domesday Book of 1086 refers to “Clipestune” with the following entry:

“Osbern and Wulfsi had 1 c.[carucate] of land taxable. Land for 2 ploughs. Roger has 1 1/2 ploughs in lordship and 12 villagers and 3 smallholders who have 3 1/2 ploughs.

1 mill, 3s [shillings]; woodland pasture in places, 1 league long and 1 wide.

Value before 1066, 60s; now 40s” (Morris 1977).

The name Clipstone means “Klyppr’s Farm”, with the derivation of the first element being from the old Scandinavian personal name “Klyppr”, and the second element from Anglo-

In the Medieval period the lordship of Clipstone and the royal palace there were located at the heart of medieval Sherwood Forest. This was the reason for the importance of the site and its subsequent expansion and development (Gaunt 2011).

“In Medieval times a forest was a defined geographic area subject to forest law. Forest law was brought to England by the Normans. The law protected beasts of the chase; primarily deer, for the king. It also protected the woodland that formed their habitat. Forest Law was enforced over the land regardless of who owned it (Turner 1901). In the 13th century the forest stretched from the River Trent in the south to the River Meden in the north and from Wellow in the east to Sutton-

Excavations in Castle Field by Philip Rahtz in 1956; Trent and Peak Archaeology Trust in 1991; Wessex Archaeology 2011; Gaunt, Wright, Crossley and Budge in 2012; and Mercian Archaeological Services CIC in 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018, have uncovered large amounts of archaeology dating from across the period of the medieval palace.

The earliest of these excavations was by Rahtz in 1956. Notable finds include a carved “Monster head” from the 12th century (Rahtz 1960), which suggests at least one stone building from this period.

In 1176-

What form these buildings took is currently not known; and it should be pointed out that at the current time the date of construction of the standing ruin is not known.

Philip Rahtz, and Howard Colvin both dated the standing ruin to the 13th century (Rahtz 1960; Colvin 1963). The pottery that can be identified in the archive, that was used in this dating has been confirmed as from the 13th -

A 12th century date for the construction of the standing ruin has recently been suggested, although the basis for this suggestion has been questioned -

It may be that the ruin dates from this period, but research is required on the ground to determine the dating.

A theory currently being discussed from archaeological results including geophysical survey, test-

From his 1956 excavations Rahtz believed that a ditch encircled the extent of the palace site (which he excavated in a number of places), although he did state that other areas of buildings could have existed away from the sanding ruin (Rahtz 1960). The Wessex report states that “it is still not clear, however, whether the ditches found by Rahtz all formed part of the same feature,” (Wessex 2011).

The profiles drawn by Rahtz (1960) of the “ditch” varied on the southern and western side of the ruins. Recent Ground Penetrating Radar survey by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC has detected the “large enclosure ditch” suggested by Rahtz (Gaunt 2015). It is possible from further examination of the data that this anomaly represents more than one feature, as it does not necessarily appear to join up with the ditch to the south of the ruin. The GPR survey undertaken by GSB unfortunately did not cover the area where the southern section and western section meet (Wessex 2011).

Despite these uncertainties with the evidence this feature has been suggested by some to represent the extent of the 12th century site (Wessex 2011; Wright 2016).

The GPR survey by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC will continue over the coming years at higher resolution. This will be published by the author (Gaunt) when complete. Until this time it will not be possible to be certain as to whether this is one single ditch feature, and it will certainly not be possible to state with confidence if it was the 12th century boundary of the site.

It should be noted that the excavations by Mercian Archaeological Services in 2014 discovered a ditch 100m to the south of the ruin that pre-

“Interestingly Rahtz recorded a ditch of markedly similar profile (Ditch 50*), (Rahtz 1960, 35), though in his interpretation he linked it to other ditches with different profiles elsewhere on the site, and tentatively interpreted them as part of a single curvilinear boundary surrounding and extending west of the ruin. The contemporaneity of the supposed curvilinear boundary to the standing ruin have since been questioned, based on the evidence presented by Rahtz in his article, and it has been suggested that the supposed enclosure may pre-

With questions over the nature of the 12th century boundaries suggested by Rahtz, and the presence of 12th century pottery outside of this feature (Gaunt & Budge 2013; Budge 2015; Budge 2016 in press); the extent of the 12th century site is as yet unknown.

However excavations by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC are beginning to demonstrate that the site in the 12th century occupied an area from around the standing ruin towards the road way to the north (Budge and Gaunt 2013; Budge 2015; Budge 2016 in press). It is hoped that over the coming years a fuller picture will emerge.

By the 13th-

This ditch was excavated by Wessex in 2011, and by Gaunt, Wright , Crossley and Budge in 2012. The 2012 excavation suggested a 13th -

The excavations in 2014 by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC also suggested that the boundary ditch was part of an extension of the palace in this period:

“Significant in terms of interpretation of the feature was the fact that the plough soil on the north side (the ‘inside’) of the ditch yielded relatively high quantities of medieval pottery, mostly of 13th-

The excavations by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC in 2014 have therefore built on previous work, and given a proven date for the ditch first detected by Gaunt in 2010 as later 13th -

The Gatehouse to the palace is first mentioned in the 14th century (Colvin 1964).

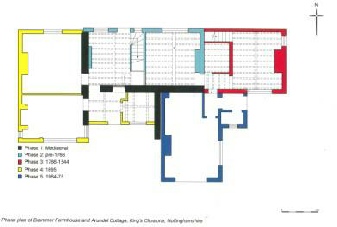

It was first suggested by Mrs M A Bradley as likely to occupy the site of the current Maun, Arundel and Brammer cottages (pers. comm) which lie on the southern side of Mansfield Road on the north side of Castle Field.

During the filming of Time Team at King John’s Palace; plaster was removed from a wall in Arundel Cottage to reveal part of a medieval wall preserved in situ. The following interpretation identifies the gatehouse, and parts of a possible curtain wall by Wessex in 2011:

“4.3.2. Observations of a small section of the rear wall of Arundel Cottage that borders the north of the site… revealed a regularly coursed wall using the same limestone seen in the upstanding remains. The regular coursing suggests that this is a medieval wall, as within a later wall using re-

”4.3.3 A pipe roll manuscript dated to 1348/9 describing work undertaken on repairs and improvements to the ‘palace’ talks of a ‘claustrum’ [barrier] encircling the manor in the north part from the great gates [gatehouse] to the angle of the field’. Maun Cottage was called The Gate Inn in the 18th century and may well be the location of the former gatehouse. The wall at the rear of the cottages is therefore likely to be part of the perimeter wall of the manor site” (Wessex 2011, pp8-

Following on from the interpretation of the cottages by Time Team (Wessex 2011) as the location of the gatehouse, (based on Mrs M A Bradley’s suggestion), Mercian Archaeological Services CIC were given permission to access and record the cottages. Subsequently a survey was arranged of Brammer Farm House and Arundel Cottage, which was undertaken for Mercian Archaeological Services CIC in 2013. This survey mapped these walls and corroborated the interpretation that they formed part of the Medieval gateway and part of the curtain wall (Wright 2013).

With the gatehouse on the northern edge, it is likely that an area enclosing some 7 acres may have formed the largest extent of the Royal Palace in the 13th-

To date; the complete boundary of the site during the 13th and 14th centuries is not fully proven, nor is the relationship to a possible site of domestic occupation within Castle Field to the northwest (Budge 2015). As with the 12th century boundary; excavations by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC are continuing into the boundaries of this once large and sprawling medieval palace (Budge 2015; 2016 in press), and it is hoped that eventually the boundaries will be understood more fully over the coming years.

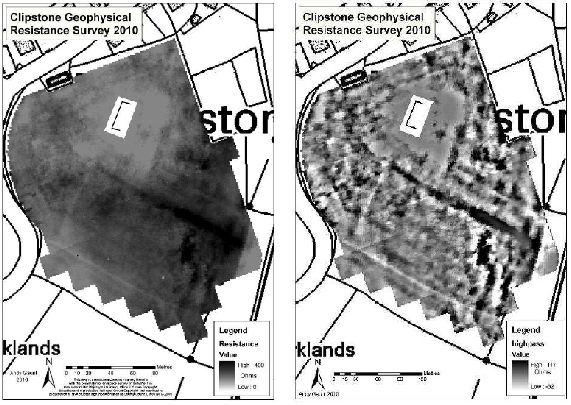

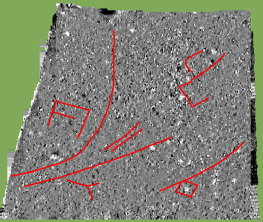

Anomalies detected through geophysical survey; including Magnetometer surveys (Masters 2004; GSB Prospection 2011; Gaunt 2017) Resistance Surveys (Masters 2004; Gaunt 2010) and Ground Penetrating Radar (GSB Prospection 2011; Gaunt 2015) have all suggested possible buildings or robbed out walls, ditches and other features, that could represent parts of the built environment of the medieval royal palace (and also any potential unknown preceding occupation).

Over the last 4 years large amounts of work have been undertaken by Mercian on the northern frontage of the palace site, revealing a wealth of information regarding this once impressive frontage. Work has also been undertaken examining the results of geophysical surveys which hint at the layout of the site within the boundaries. Including possible courtyard areas and a range of buildings on the alignment of the standing ruin. Details will be released in due time.

Post Medieval

The King’s Houses at Clipstone began a rapid decline from their heyday in the 13th and 14th centuries. Diminishing royal interest in the 15th century manifested itself in no further visits by any monarchs following the reign of Richard II. This decline of royal interest in the King’s Houses throughout the 15th century fits an overall national pattern. Steane has pointed out that the residences of the monarchy in the later middle ages focused on southeast England. Additionally the numbers of palaces and castles under direct royal control dwindled, and as the size of the Household increased from c.120 in the reign of Henry I to 800 under Henry VI fewer but more grandiose palaces were the preference (Steane 2001).

A survey of the "the dekayes of the manner of Clippeston" dated to 1525 (National Archives E 178/4394) records that:

“First the southest end of the hie Chamber ther is in great dekay & ruyne in stonework tymber lede and plaster & the gavell ende of the same is flede outwarde so that a part of the rove and of flour of the said Chymber is fallen doune. Also ther was sume tyme begone a stone grees & yet is not fynyshed the which hath been the cause of the Ruyne of the said Chambre. Also the Chappell ther is in dekay and hath no cuverying upon it. Also the kechyn ther was new plasterid and the rof therof wantith poyntyng and amedyng of the slate, also on the said kechyn were ij chymnays begon and not fynishyd” (Colvin 1963)

“This survey only lists 3 structures: a chamber, a chapel and a kitchen. It is impossible to be certain whether or not this represented the only extant above ground buildings by 1525, but clearly there was a rapid period of decline” (Gaunt et al 2015).

A land grant of March 1568 refers to the “site of the late castle”, and it seems clear that substantial clearance of the ruins had occurred by this date (Ministers Accounts: SC6 Philip & Mary/505(Notts); Gaunt et al 2015).

The documentary evidence for ruin and decay is perhaps confirmed by the archaeology: excavations by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC in 2013 found evidence of ‘recycling’ of palace material by one of the villagers in the post medieval period:

“Here a small, early post medieval , pit was found dug into the natural sands. A quantity of medieval window glass had been dumped in the pit before it was backfilled. The majority of the glass was plain and included some largely complete quarries (with very neatly grozed edges), but a small quantity of painted glass was also present. Both cylinder and crown techniques of manufacture were present and more than one phase of glazing, or more than one window seems likely to be represented. It seems probably that the villager living on this plot ‘liberated’ a window or two from the palace as it was falling into disrepair in the early post medieval period with the aim of harvesting the lead. Perhaps not having the technology to recycle the glass or not having easy access to a market for it, they dug a hole in order to conceal the evidence of their crime!” (Budge & Gaunt 2013).

The Designed Romantic Medieval Landscape:

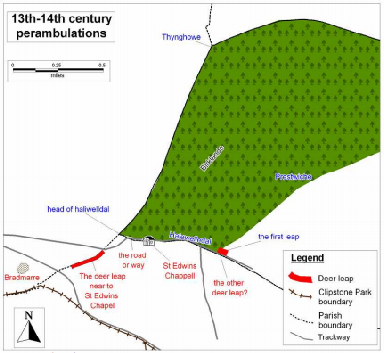

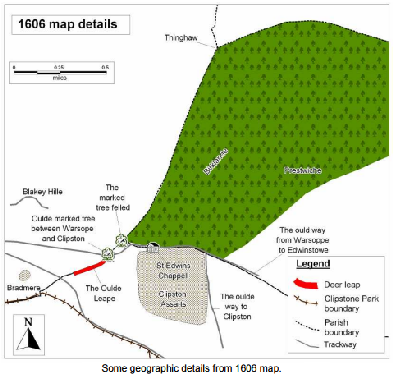

The Medieval Landscape of Clipstone was a designed landscape, altered by the crown to form an idealised Forest in Miniature, suitable from Royal Hunting. The layout of this landscape seems to suggest a design reflected in the depictions of landscape in contemporary literature, such as that depicted in the 14th century Arthurian poem Gawain and the Green Knight (Gaunt 2011; Gaunt & Wright 2013).

In 2006 Andy Gaunt began working on creating a map of the landscape of medieval Sherwood Forest, with Alan McCormack (former Keeper of Antiquities at Nottingham Castle), while working as a Community Archaeologist at Nottinghamshire County Council. This mapping helped Gaunt form the beginning of what would develop into a deep and intimate knowledge and understanding of the landscape of Sherwood Forest, particularly in the Medieval period. In 2009 the act of Gaunt standing on top of the ruins of King John’s Palace, during restoration work, and observing the relationship of the site to the surrounding woodlands, led to investigations into the historic mapping and documents, and relating them to the actual landscape through surveying and field work.

Picture: Andy Gaunt on top of the ruins of King John’s Palace, looking at the views, circa 2009.

Picture: Andy Gaunt on top of the ruins of King John’s Palace, looking at the views, circa 2009.

This in turn led in 2010 to a Geophysical Resistance survey of the 11 acres of Castle Field (Gaunt 2010) with the intention of understanding the layout of the palace, in order to create a 3D model of the site, and relate the palace to the landscape in ArcGIS through 3D modeling. This survey led to a new interpretation of the palace site as being the same or similar to the 6-

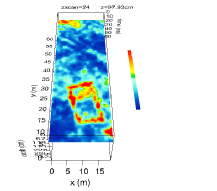

Picture: Gaunt 2010 geophysical resistance survey results

This formed the basis of a subsequent Masters Dissertation; Clipstone Park and the Kings Houses-

Picture: Andy Gaunt’s 2011 dissertation Clipstone Park and the King’s Houses: Reconstructing and interpreting a medieval landscape through non-

This work represented a multi-

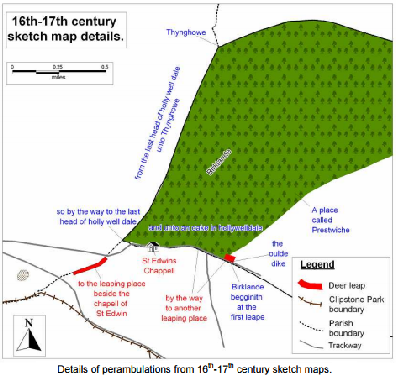

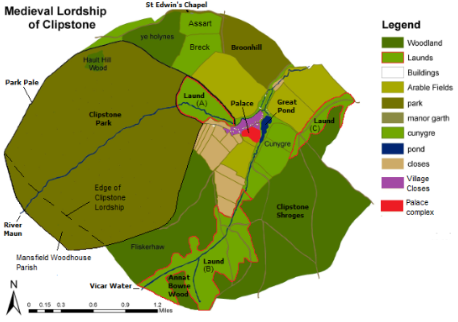

Picture: Landscape analysis -

Picture: Landscape analysis -

Picture: Landscape analysis -

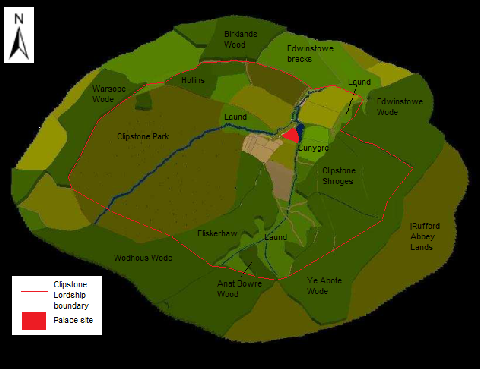

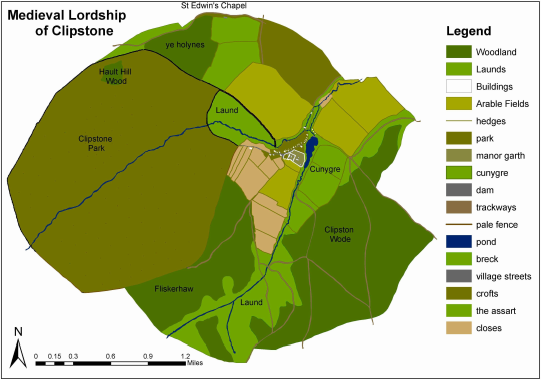

The resulting landscape analysis (computerised GIS based reconstruction of the landscape of Clipstone in Medieval times based on the 1630 map by William Senior, and other historic mapping and documents, and computer generated 3D models) enabled a theoretic examination of the landscape.

Picture: 3D reconstruction of the palace site (Gaunt 2011).

Picture: 3D reconstruction with analysis of Resistance survey results (Gaunt 2011)

Picture: Reconstructed medieval landscape of Clipstone and surrounding landscape. (Gaunt 2011).

This was the first full interpretation of the landscape of Clipstone (David Crook wrote about the landscape of Clipstone in his publication Clipstone Park and Peel (1976), but Gaunt’s 2011 work was the first fully integrated multi-

Picture: Gaunt’s reconstruction of medieval Clipstone in 2D (Gaunt 2011).

All subsequent landscape discussions at Clipstone are based on this work.

From this quantitative study of the landscape it became apparent to Gaunt that the medieval landscape at Clipstone should be compared to other large royal palace sites in the country such as Clarendon and Woodstock, and abroad such as Hesdin in France.

Work by eminent academics including Dr Amanda Richardson on medieval deer parks and hunting landscapes has suggested that landscapes around high status hunting palaces have an element of design, some of which reflects the desire to create landscapes similar to those depicted in the Romance literature of the times (Richardson 2007).

The GIS reconstruction created by Gaunt (2011) enabled a more qualitative interpretation to be undertaken in a quantitative environment, as suggested by Henry Chapman for using GIS in Landscape Archaeology (Chapman 2006). Using this computer simulation and analysis work alongside on-

Following further development by the author (Gaunt), including more on the ground interpretation these were published in the Thoroton Transactions by Gaunt (with some contributions on the built environment by Wright (Gaunt and Wright 2013).

Elements of design recognised by Gaunt in the medieval landscape include: Launds, Holynes (A wood of Holly trees for fodder for fallow deer in the park), Cunygre (rabbit warrens), Clipstone Wode, Fliskerhaw Wode, the Great Pond, and other features, including the medieval open fields, and possible relationship of the palace site to the mannorgarth (Gaunt 2011).

Picture: Gaunt 2011 map redrawn by Gaunt for 2013 publication in Thoroton Society Transactions (Gaunt & Wright 2013) with extra annotation and Launds higlighted.

The following excerpt from Gaunt 2011 demonstrates elements of the designed landscape of Clipstone including the relations of the palace to the deer Launds, and the topography and surrounding wood and Forest:

“The landscape of Medieval Clipstone is very much dominated by the park and royal palace site. The Palace site occupies the head of a spur of land created by the confluence of two rivers. As well as the complex of buildings which make up the palace the site also extends to the south to include an area of rabbit warrens across the valley of Vicar Water, and to the east to include the large fish pond, and a stew pond for storing fish ready for the table within the complex itself. The Palace site is situated on a rise above the village which is level with the approach from the northwest, and the royal manor of Mansfield. It becomes visible when the roadway turns to face the palace. Views from the palace in this north-

All the views from the palace on the north, west and southern sides are framed by woodland at their furthest view. This gives an impression of being in a wild and wooded environment, a back drop for the palace and parkland. It has been suggested that such a setting and the use of views was an essential part of the make up and use of medieval parks. ‘They provided wood and especially timber, or grazing for horses, or many other practical uses, but crucially they still existed as an ornament and provided a private place of recreation in the full meaning of the word’ (Fletcher 2007). Beyond just being functional sites that were by chance also beautiful parks can be viewed as ‘ornamental landscapes’ (Taylor 2000). This suggests perhaps a deliberate maintenance or even manufacture or design of the landscape to be ornamental. In the absence of much discussion available from the historic records which are by their nature concerned mainly with the recording of expenses and building costs, attention has focused more recently on romantic literature. Examples such as the depiction of Bertialk’s castle in Gawain and the Green Knight have been suggested as a source of inspiration for park land creation and the retreats of medieval kings, or as a reflection of an ideal. The ideal being parkland surrounded by the wild wood and containing expansive launds used to frame whitewashed palaces (Richardson 2007). Similar royal residences have been shown to back up this view that the landscape was used as a backdrop to be enjoyed. The intention of Henry I in his efforts at Woodstock seems to have been as much to create a comfortable retreat as to make a statement of power and authority (Mileson 2007). Edward III also seems to have made additions to Woodstock palace with the intention of enjoying the beauty of the landscape, with a reference to a balcony being constructed in 1354 in order to provide his daughter Isabella with better views over Woodstock Park (Colvin 1986). Such a consideration would seemingly not be made if the landscape was merely one of function or status. A recent reconstruction of Clarendon Palace by English Heritage shows the residence to be raised on a steep scarp above a valley from which the northern launds rise. ‘Visitors would see the palace scarp terrace dominating the skyline, backed by trees, and would have to climb the hill to the western entrance having traversed the park below’ (Richardson 2007). This description is very similar to the landscape and palace at Clipstone, especially the approach from the northwest.

It is necessary to be cautious when suggesting that the park and palace were designed to operate together, due to the difficulty in stating a single designer for a park such as Clipstone. It seems more likely that the park, palace and landscape developed in unison in a piecemeal fashion through the medieval period. But what does seem apparent from examining the medieval landscape is that the palace was developed to take advantage of its setting. It would be hard to imagine that this was not done with a romantic ideal or an appreciation for beauty and the setting within a landscape of hunting and perceived romance”. (Gaunt 2011).

Picture: View from approach from the East. Andy Gaunt’s 3D reconstruction of medieval romantic landscape of Clipstone (Gaunt 2011).

Picture: View from the southeast. Andy Gaunt’s 3D reconstruction of medieval romantic landscape of Clipstone (Gaunt 2011).

Picture: View from the Northwest. Andy Gaunt’s 3D reconstruction of medieval romantic landscape of Clipstone (Gaunt 2011).

Picture: View from the southwest. Andy Gaunt’s 3D reconstruction of medieval romantic landscape of Clipstone (Gaunt 2011).

Picture: Views from the northwestern deer laund of the palace (Gaunt 2011).

Picture: View from the laund to the east-

The landscape of Clipstone was identified by Gaunt as being similar to that depicted in the Gawain and Green Knight poem.

There is possibly also evidence to back this up with relation to the built environment at Clipstone: Saltzmann in his 1952 book Building in England Down to 1540 A Documentary History actually states the following:

“In 1368, at Clipstone, we find a payment ‘for making 2 chimneys (camenorum) with plaster of Paris, which had blown down by the wind (Salztmann 1952)”… He states that the entry comes from the King’s Rememberancer, Accounts roll E101/460/20, and continues: “...-

If this is a true interpretation by Saltzmann and Addy relating to interpreting Plaster of Paris Chimneys at Clipstone to those depicted in Gawain and the Green Knight, this goes some way to corroborating Gaunt’s interpretations of the designed romantic landscape of Clipstone, and suggests that this romantic design was mirrored in the built environment of the palace.

More recent interpretations based on the results of excavations of test-

Along with the establishment of the park in the 12th century, and the presence then of the Great Pond, Gaunt has suggested the parkland landscape and many of the elements of this designed Arthurian landscape, actually stretch back to the earliest royal developments in the late 12th to early 13th century landscape (Gaunt 2017 http://www.mercian-

It is worth noting that the Gawain and Green Knight poem merely reflects the ideals of the times, which are themselves reflected in the landscape at Clipstone.

The Arthurian influence on landscapes is far earlier than the 114th century poem, with interest stretching back to the 12th century, from authors such as Chrétien de Troyes.

Unfortunately other authors who have used Gaunt’s work (eg Wright 2016) may lead people to believe the landscape is 14th century in origin. As suggested by Gaunt, this is not true and there are elements of that landscape as shown which are 12th and 13th century.

Archaeological Work at King John’s Palace and Clipstone:

The site of King John’s Palace and surrounding landscape of Clipstone have been subject to a number of archaeological investigations which are recorded below.

2013-

2019 Archaeological Training Field School, King John’s Palace, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

A second season of excavation occurred on the northern boundary of the site, in the grounds of the building known as the Tin Tabernacle… “Provisional results suggested that a medieval structure was located. What appeared to be the foundation for a wall was encountered running south west to north east. This was formed from a compacted deposit of rubble… which may have been in a shallow ditch or gully.To the north of the probable foundation a sequence of deposits appeared to represent the interior of the building… The deposit was not horizontal: it sloped from north to south. It seems extremely unlikely that the sand of the geological substratum was left exposed as the internal floor surface especially as it was not level. It is possible that some of the pebbles found within the dirty sand deposit represented the remains of a robbed out cobbled floor; the geological substratum in this location appeared to be devoid of the pebbles often found in the Sherwood Sandstones suggesting that they were brought to this location rather than deriving from underlying deposits. Lying on top of the dirty sand deposit were quantities of Mansfield red dolostone fragments. These were all roof slates. All were broken but the more complete examples showed a range of sizes and thickness and many featured original mortar. The angles at which they were lying suggested that they had probably fallen or been dropped from a roof.” (Taken from Budge 2019).

2018 Archaeological Training Field School, King John’s Palace, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

Excavation occurred on the northern frontage of the site, in the grounds of the building known as the Tin Tabernacle. To the east of the trenches from 2015-

This initial phase of work in this location featured on Channel 5 in the “Digging Up Britain’s Past -

Picture: Andy Gaunt interview with Alex Langlands.

Picture: Andy Gaunt interview with Alex Langlands.

2017 Archaeological Training Field School, King John’s Palace, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

A third season of excavation occurred in a trench close to the road frontage of the site, in the grounds of the building known as the Tin Tabernacle.

2016 onwards: “From Rahtz to Mercian” -

Mercian Archaeological Services CIC are undertaking a re-

(Picture of the 12th century carved Beast head excavated by Rahtz in 1956)

2016 Archaeological Training Field School, King John’s Palace, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

A second season of excavation occurred in a trench close to the road frontage of the site, in the grounds of the building known as the Tin Tabernacle.This part of the site “may contain some of the only surviving remains of the road frontage of the palace, while the lack of 20th century ploughing may mean any remains are well preserved. The most significant finds, however, came from the re-

2016 Ground Penetrating Radar Survey at King John’s Palace, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

This GPR Survey continued the survey from 2015 with further coverage to the east and southeast of the monument. The results will be published at the end of the project, in line with Mercian Archaeological Services CIC’s publication policy.

2015 Archaeological training Field School, King John’s Palace, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

The first season of excavation occurred in a trench close to the road frontage of the site, in the grounds of the building known as the Tin Tabernacle.This part of the site “may contain some of the only surviving remains of the road frontage of the palace, while the lack of 20th century ploughing may mean any remains are well preserved. The most significant finds, however, came from the re-

2015 Discover King John’s Palace -

This test-

2015 Ground Penetrating Radar Survey at King John’s Palace Phase 1, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC:

This GPR Survey covered the area to the north and west of the monument, and is the first part of a survey designed cover the entire site in multiple levels of resolution over a five year period. The results will be published at the end of the project, in line with Mercian Archaeological Services CIC’s publication policy. Preliminary results are published in Gaunt 2015.

2014 Archaeological Training Field School, King John’s Palace, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

The 2014 field school focused on the intersection of geophysical anomalies representing possible ditches (Gaunt 2017). The excavation confirmed the dating of the medieval boundary ditch. An older ditch (possible enclosure) in the southwestern corner of Castle Field, was cut by the boundary ditch of the palace. It was suggested that this ditch/enclosure pre-

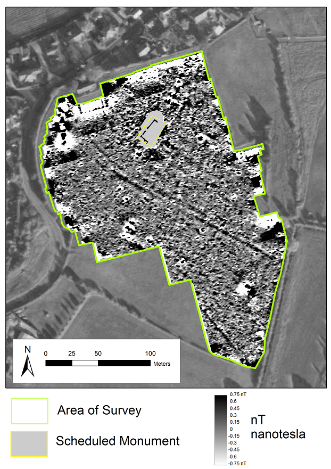

2014 Geophysical Magnetic Survey at King John’s Palace, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

This survey covered the whole of Castle Field, and detected anomalies including the boundary ditch (Gaunt 2010; Gaunt 2011; Budge 2014a, Gaunt et al 2015), and possible buildings. The results are published in Gaunt 2017.

Download the report here:

Geophysical Magnetometer Survey at King John’s Palace in Sherwood Forest.

Geophysical Magnetometer Survey at King John’s Palace in Sherwood Forest.

Castle Field, Waterfield Farm, Kings Clipstone, Nottinghamshire.

Andy Gaunt

http://www.mercian-

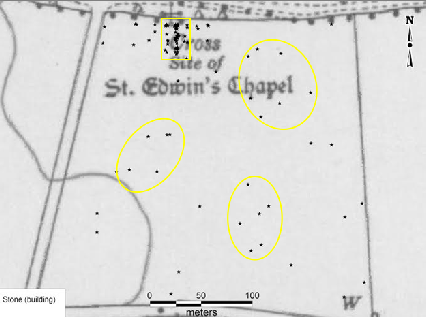

2014 St. Edwin’s Chapel, Kings Clipstone, Fieldwalking, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

This survey covered the field to the south of St Edwin’s Chapel. The fieldwalking helped to confirm the location of the chapel through the presence of scattered building stone. Finds within the spread of stone included 13th-

2014 St. Edwin’s Chapel Geophysical Magnetic Survey, Kings Clipstone, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

The field south of St Edwin’s Chapel was subject to a Magnetic Survey. Unfortunately conditions and problems with equipment resulted in poor results. The site is due to be re-

2014 Standing Building Survey of Maun Cottage, for Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

A survey of Maun Cottage was undertaken by James Wright on behalf of Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

No report exists for this work or has been received, and no communication has been received following the expiration of a negotiated deadline of April 2016.

2013 Digging the Demense, Test pitting project in Castle Field, by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

This test-

Recent work at King John’s Palace, Clipstone, identified a geophysical anomaly (Gaunt 2011) which was demonstrated by excavation to have been constructed in the 13th – 14th century and which probably formed the western boundary of the palace complex at this time (Gaunt et al 2015). The boundary is depicted on a 17th century map with the land to the northeast marked as “Manor Garth” and that to the southwest as “Waterfield” (1630 map by William Senior (NAO, CS/1/S)).

As part of the Sherwood Forest Archaeology Project, local volunteers supervised by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC excavated six 1m square test pits to the west of the boundary ditch, within the northern part of Waterfield, over four days in August 2013. The purpose of the investigation was to determine if there was any difference in the nature and character of archaeological deposits to the southwest of the boundary ditch and those encountered in previous interventions to the northeast, in Manor Garth. Due to the light sandy soils and the approximate 10m decrease in elevation from west to east of the field, the test pits were additionally intended to assess the potential for survival of archaeological deposits at the top, middle and near the bottom of the slope.

Download the Interim Report here:

“Digging the Demense”, Community Archaeology Test Pitting Project, at Waterfield Farm, King’s Clipstone, Nottinghamshire. Interim Report.

“Digging the Demense”, Community Archaeology Test Pitting Project, at Waterfield Farm, King’s Clipstone, Nottinghamshire. Interim Report.

David Budge

2013 King Clipstone Village Project by Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

Test pitting in village to investigate settlement development,This project excavated test-

2013 Standing Building Survey of Brammer Farm House and Arundel Cottage, for Mercian Archaeological Services CIC.

This survey was undertaken on behalf of Mercian by James Wright, and confirmed the presence of a medieval wall (previously interpreted by Wessex Archaeology), and related the wall to the theory that the remains possibly formed part of the Gatehouse of the Palace. The report is available on Mercian’s Publications Page.

2009 -

2012 Boundary Ditch Excavation

This project opened two trenches across the linear anomaly identified by Gaunt (2010) and suggested as the boundary of the “Mannorgarth” (Gaunt 2011). “The anomaly proved to be a substantial ditch. Though there were relatively few finds, the ditch appeared to have begun silting in the 13th or 14th century, with pottery of a similar date being incorporated into the base of the possible bank deposits located to the north of the feature (inside the palace complex) and thus suggesting a 13th or 14th century date for its construction. The ditch remained in use as a land parcel boundary after the palace was decommissioned and the upper fills included various post medieval and modern ceramics” (Gaunt et al 2015). The excavation was undertaken by Andy Gaunt, Sean Crossley, David Budge (now Mercian Archaeological Services CIC) and James Wright.

2011 Time Team excavation. Wessex Archaeology.

Seven trenches were excavated by Wessex Archaeology on behalf of Videotext Communications Ltd during April 2011. The majority of these lay close to the area of the Scheduled Monument. The Time Team excavations were the first major archaeological excavations within the site of the medieval royal palace at Clipstone. Although there are problems with the pottery dating for the Medieval period, (discovered during a re-

To the northeast of the standing remains, a rectangular building to the north of the standing ruins, but on a different alignment to them, was excavated (Wessex 2011, Brennan 2015).

Other possible walls and features were not excavated but were recorded in the geophysical surveys below. The full report can be found in Wessex 2011, and a publication of the results is seen in Brennan 2015.

2011 Ground Penetrating Radar Survey and Magnetometer Survey, King John’s Palace, GSB Prospection.

Undertaken during the filming of Time Team at King John’s Palace in April 2011. Amongst the anomalies found was a rectangular response that was subsequently interpreted as a chapel by Wessex (Wessex 2011), also walls to adjacent to the northwest face of the standing ruin (Wessex 2011) these probably relate to the “Tower” suggested by Rahtz (1960), and a number of potential walls orientated parallel and perpendicular to the standing remains were detected on the southeast side of the monument, some of these walls were excavated (Wessex 2011).

The results of the survey although “frustrating” according to the report, have helped to located a large number of possible walls in and around the monument, that are the first major starting point in understanding more of the layout of the site, and are therefore a great asset to the archaeological record.

2011 3D and 2D Archaeological reconstruction of medieval designed romantic landscape of Clipstone, Andy Gaunt:

In 2011 Gaunt undertook a reconstruction of the landscape of medieval Clipstone in GIS and 3D software with data from the 1630 map of the lordship and other historic documents. (Gaunt 2011). This reconstruction in 2D and 3D and the accompanying reporting constituted the first major analysis of the landscape as a whole.

2010 Geophysical Resistance Survey, Andy Gaunt:

This survey by Gaunt covered the entire 11 acres of Castle Field. It was the first geophysical investigation on the site to cover the whole field, and not targeted merely on the immediate proximity of the standing ruins. The survey aimed at determining the boundaries, extent, and possible built environment of the site. The survey detected a number of anomalies that could represent parts of the built environment, as well as possible garden features. The main anomaly detected was a 160m long anomaly running northwest-

Picture: Results of Resistance survey Gaunt 2011.

Download Andy Gaunt’s Resistance Survey Report:

http://site.nottinghamshire.gov.uk/EasysiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=131123

2009 Level One Survey of parish by Andy Gaunt and research for MA.

Recorded the location of boundary oaks, and the suggested deer leap in Kings Wood to the north of the parish (Gaunt 2011).

1991 -

2008 Condition Survey of Monument by Peter Rogan (Chartered Architect and Historic Building Consultant) (Rogan 2008).

2008 Stone Amnesty, Nottinghamshire County Council.

The report for this Nottinghamshire County Council 2008 project, led by James Wright, remains unwritten.

2004-

Photographic record, condition survey and structural analysis of monument. The results can be seen in Mordan and Wright (2005), and Wright (2004).

2004 Geophysical Resistance and Magnetometer Survey by Peter Masters, PCA Archaeology.

This identified a number of linear anomalies identified as robbed out foundation trenches, ditches and traces of earlier excavations (Masters 2004).

1991 Archaeological Investigation by Trent & Peak Archaeology.

Excavations within the Scheduled Monument as part of reconstruction work to the ruin. The report was published in 2016 by Richard Sheppard.

The excavation’s study area was set beneath “a gap about 5.5m long in the main north-

1991 Fieldwalking of Castle Field by Trent & Peak Archaeology.

One exceptional find was a jetton, found at “some distance” from the monument (No report, exists-

1950s, Earlier excavations:

1956 Evaluation excavations conducted by Philip Rahtz.

In October 1956 Philip Rahtz excavated 2 long evaluation trenches extending outwards at right angles to the monument through its centre. A number of smaller trenches and inspection slots were also excavated in an attempt to trace features such as a posited boundary ditch. Finds included a possible Roman feature, post holes, pits and possible beamslots from the 12th or early 13th century. Rahtz interpreted the ruins as dating from the later 13th century based on archaeological finds.

Historical Timeline for the Medieval Kings Houses at Clipstone:

As archaeological work continues to establish the boundaries of the site, and attention turns to understanding the built environment of the palace complex through Geophysical Survey and excavation; the historical timeline for the site is reasonably well understood.

Publications by Howard Colvin in the 1960s (concentrating on the building records), and David Crook (listing the visits of the Kings to the Palace, and focusing on the deer park) in the 1970s; building on and adding to Stapleton’s work in the 1890s have helped to create a baseline data set and timeline for the site.

Recent publications by Gaunt (Mercian Archaeological Services CIC) have further helped in the understanding of the written record for Clipstone.

Also local community research concentrating on the records from the various court rolls for the site (notably by Josh Down of the Forest Town Nature Conservation Group (references from Josh Dowen’s site are marked with a link to the Forest Town Nature Conservation Group page http://www.foresttown.net/index.php/heritage/clipstone-

The various court rolls, building records, patent rolls, liberate rolls etc covering the entire period of the sites occupation are published. Some of these are available online, and others in archives.

Mercian are also fortunate to have original full copies of the Nottingham Borough Records, Sherwood Forest Book, History of the King’s Works, Inquisitions Post Mortem, Thoroton Society Transactions, and many other sources for the site in their library.

Below is a timeline of events collated from Court Rolls, Liberate Rolls, Patent rolls, published secondary accounts by Historians, and many other sources; and represents some of the recent research.

Mercian consider that this historical research should be available to the public in order to raise the profile of the site, and help to demonstrate the importance of the site in medieval times.

It is hoped it will be of interest to anyone wanting to know more about the palace, and that it will be of use to anyone looking to undertake further research.

The list should be considered to be dynamic, and is being compiled and updated constantly from our baseline data sets on the Mercian network. We promise that all will be available eventually.

(please forward any questions or comments to info@mercian-

Norman

1086: Domesday Book:

“Osbern and Ulsi [Wulfsi] had two manors in Clipstone, which paid the Geld for one caracute. The land was two caracutes. After the Conquest Roger de Busli had in demesne one caracute and a half, and twelve villeins and three borders, having three caracutes and a half, and one mill of three shillings. Wood, by places pasturable, one leuca long and one broad. In the Confessor’s time the value was sixty shillings, but forty shillings at the time of the Survey.”

Henry II

1164-

1164: This year, for a tun of wine for the King, and its conduct from London to Clipstone, and thence to Nottingham, was paid £4 12s. 6d., perhaps in connection with a royal visit. In works upon the Kings' House at Clipstone £20, by the King's writ. And for a fourth of the year, while Robert fitz Ranulph held office, £13 8s. 6d. (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1165-

1166-

1168-

1170-

1171-

This is the earliest reference to the Hays. The word itself means a hedge, but here it signifies an enclosure,—always occurring in the plural. The number however is not mentioned, but there were probably two, perhaps one within the other with a view to defence. The hays of Sherwood Forest were enclosures in which no man could claim commonage.

The phrase "by view" requires a little explanation. When the sheriff of a county executed, by order, any work for the King, the amount expended was set down to his credit, to be settled for at the end of the official year. But, to save the King from being overcharged or defrauded, "viewers" were appointed to oversee the work. The number of these is not often mentioned,—though they are specially set down as four in 1214; it probably varied, perhaps in proportion to the magnitude of the work. These were mostly agents of the Grown, royal taskers, purveyors and the like,—at times local jurats,—who were afterwards examined before the Barons of the Exchequer on their oaths, before the Sheriff was finally credited to the amount expended (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1173-

1176-

1177-

1178-

1179-

1176-

Building of a chamber and a chapel

Construction of a fishpond

Formation of a deer-

(Colvin Vol II p918)

No architectural details, but the beast head “twelfth-

The Angevin house was surrounded by a ditch, partially excavated in 1956 (see rahtz) (Colvin Vol II p918).

Colvin possibly misidentifies the fish pond as the earthwork surviving adjacent to castlefield. Or he may be right! (Colvin Vol II p919)

For some time after the death of Henry II the expenditure was chiefly on repairs (Colvin Vol II p 91)

1178 -

1181: August (Eyton, R. W. 1878. Court, Household, Itinerary of King Henry II. Taylor and Co. p241).

Henry II visited Clipstone (Crook , D. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80).

The King was at Nottingham about August 1181, whence he probably journeyed north (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

“A charter to the order of Lazarites, bearing date at Clipstone, very possibly belongs to this period. It is attested by Geoffry the King's son, Fulk Painel, Reginald de Curteneye, Robert de Stuteville, Ralph fitz Stephen, Bertram de Verdon, Michael Belet, and William de Bendinges” (Eyton, R. W. 1878. Court, Household, Itinerary of King Henry II. Taylor and Co. p241).

1182-

1184-

1185: February. (Eyton, R. W. 1878. Court, Household, Itinerary of King Henry II. Taylor and Co. p261).

Henry II visited Clipstone (Crook , D. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80).

“Of two charters there expedited one is to Thurgarton Priory, Notts., the other to Barling's Abbey, Lincolnshire. The testing clause of the latter, when corrected by the former, gives witnesses common to both, viz., Hugh, Bishop of Durham; William, Earl of Arundel; Ranulph de Glanvill; Bernard de St. Wallery; Roger de Stutevill; William de Stutevill; Hugh Bardolf, Dapifer; and Ranulph de Guddinges” (Eyton, R. W. 1878. Court, Household, Itinerary of King Henry II. Taylor and Co. p261).

This appears to be the only other recorded visit of Henry, but it is probable that he was here on other occasions, though the sparse records and chronicles of this reign afford but general ideas of the royal progresses. He frequently traversed the neighbourhood in passing between the north and south of the kingdom, and in 1157, for instance, he spent a long period from September to December in Notts, and the Peak (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1185-

1186-

1186 -

Richard I

1189: John ,Count of Montain (lthe later King John), visited Clipstone when he owned the royal estates in Nottinghamshire (Crook, D. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society Vol. 80. P 44).

1194: March 29th “in the words of an early chronicler—Richard proceeded to view Clipstone and the Forest of Sherwood, which he had never before seen, and they pleased him much, and on the same day he returned to Nottingham” (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1194: April 2nd Richard I visits Clipstone and meets William the Lion King of Scotland. “ the King again proceeded to Clipstone to meet William, King of Scotland there, ordering, in the meantime, that all who were lately taken in the castles of Nottingham, Tickhill, Marlborough, Lancaster, and Mount St. Michael, should be brought together at Winchester, on the morrow after Easter”.

The following day, 3rd April, being Palm Sunday, the King remained at Clipstone on that account.

1194: Richard I visits followed by repair to the fish-

1194: John ,Count of Montain (lthe later King John), visited Clipstone when he owned the royal estates in Nottinghamshire (Crook, D. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society Vol. 80. P 44).

King John

1200: March 19th King John Visits Clipstone http://neolography.com/timelines/JohnItinerary.html

‘John's first visit to Clipstone as King took place in the first year of his reign. He was here on 19th March, 1200, and dated hence his charter to Nottingham, confirming grants made by him while Earl of Mortain. The following list of witnesses was appended thereto, and will be of interest as recording some few of the influential nobles in his company:—"Geoffry Fitz-

1200: November 20th King John Visits Clipstone http://neolography.com/timelines/JohnItinerary.html

1200: During this same regnal year, in 1200, the men of Mansfield, commendably anxious to recover a lost right, offered the King fifteen marks for having Common of Pasture in the Park of Clipstone, as they were wont to have in the time of King Henry (II.) father of that King (John) before it was inclosed to make a park. At this time all favours, however just, requested of the King had to be accompanied by presents. Fifteen marks—a mark being two-

1201: March 6th -

“The King again called at Clipstone this year, on 6th March, in which month four out of five of his recorded visits took place. We have, doubtless, a reference to this visit in the account of William Brewer, Sheriff, this year, in which occurs the cost of carrying the King's bacons from Clipstone to Northampton, 10s. 10d., and to the Chaplain of Clipstone 20s. of his livery, from the Sunday next before the feast of St. Nicholas (St. Nic. 6th Dec.) until the Sunday next before the feast of the Ascension (Ascen. 18th May in year 2) by the King's writ, and likewise 20s. to him from that time till St. Michael (St. Mich. 29th September.)” (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1204: At the latter end of this year, on 26th December, while at Tewkesbury, the King sent to the Sheriff of Notts., ordering him to procure out of his ferm,—the county ferm,—so much as was necessary for the repair of the Houses of Clipstone, by view, &c., the amount to be computed to him, &c. The plural, Houses, is constantly used in writs of this character, and itself conveys an impression of what the place was probably like— a collection of buildings for every purpose, perhaps added to a central or main structure as occasion arose, without fixed design; and at a short distance, within the Hays, the necessary buildings and outhouses of a mediaeval farm with houses or huts for the men (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1204-

1205: March 10th King John visits Clipstone http://neolography.com/timelines/JohnItinerary.html

he King paid his third visit this year on 11th March[?] It was doubtless on this occasion, and for the royal table, that the Sheriff conveyed wine here. For on 28th September following the King, while at Nottingham, directed his writ to the Barons of his Exchequer, ordering them to reckon with that official for that which he had expended in carriage of wine from Nottingham to eleven places, including two tuns to Clipstone (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1205: Chapel of St. Edwin endowed by King John (Crook , D. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80. p35).

1206: The King on 10th March, while at Nottingham, directed the Barons of his Exchequer to reckon with the Sheriff for what he had expended—by the King's command and by view and testimony of legal men—in repairing the Houses of Clipstone (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1207: The King on 23rd May, being at Doncaster, directed his writ to Greoffry de Jorce, commanding him to release to Philip Minekan, or Munekan, the Houses of Clipstone, with the Hays, and the custody thereof, as also twenty librates of land, or land of the annual value of twenty pounds, which were formerly Ivon de Fontibus', but which were afterwards committed to him and Richard de Lexington. (The two latter are mentioned as Foresters two years earlier.) The said Philip was to have only 100s. to sustain him in the King's service, and was to answer to the King concerning the residue and concerning the Vill of Clipstone (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1207: On 28th July following, the King, while at Burton, sent intimation to Brian de Insula that he had commanded John fil Jordan, of Boston, to liberate unto him, or to a certain messenger, sixteen dolia or casks of the King's wines which were in his custody, to wit, twelve dolia of wine of Wascon' and four of Muisac'. Of these the said Brian was to convey three tuns of wine of Wascon' and one of Mussac' to Clipstone, and more to Scrooby, Lexington, and elsewhere. A dolium of wine contained fifty-

1207: On 12th October following, from Marlborough, the King commanded his Barons of the Exchequer to settle with the creditor for fifteen dolia of wine, bought at need or occasion, and of which he had caused four dolia to be sent to Harestan and three to Clipstone,—others to Lexington, Southwell, Newark, Gringley, &c. (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1207: The King at the end of the year, on 27th December, being at Windsor, sent to the Sheriff of Notts., commanding him to allow to Philip Munekan money from the county ferm for the reparation of the Houses and Dam of Clipstone, which were in the custody of the said Philip (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1208-

1210: It is an unfortunate circumstance that the series of rolls from which many of these notes are taken, and by which the whereabouts of the King at almost any date may be discovered, are broken at this interesting period by the loss of those for the period of four regnal years—1208— 1212. Another kind of roll, however, for one year, the twelvth, 1210—11, is fortunately preserved, by which happily we are enabled to record another royal visit here. John was at Nottingham in November, 1210, for several days and until Tuesday in the feast of St. Andrew, which latter day is 30th November. On the Thursday following he was at Clipstone, whence he advanced half-

1211: December 2nd -

1212: Legendary reference to Parliament Oak:

“This is the year by which, perhaps, Clipstone is best remembered by most of us. The well-

Whatever may be the truth about this alleged deed of John's, I am afraid the idea of its connection, in any way, with Clipstone must be relinquished. None of the chroniclers, so far as I can find, record such a detail. Rapin, the authority sometimes given, does not connect the story with Clipstone. In short it seems more than probable that some local writer has connected the so-

1214: August 8th Robert de Lexington, during the King's absence in France, was commanded by a deputy to cause what was needed to be done for the repair of the Lord King's Houses of Clipstone, by view of four lawful men,—whatever was so expended to be accounted to him at the Exchequer (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1215: January 11th while at the New Temple, London, commanded the Sheriff to provide payment for the two chaplains at Clipstone and Harestan, there ministering, by his command, for the soul of King Henry, his father. This note is of interest as the first intimation of the Chantry here, founded apparently by John (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1215: While the King was at Litchfield, on the 2nd April, he directed his writ to the Barons of his Exchequer, ordering them to reckon with Brian de Insula for that which Philip Monekan, sometime Keeper of his Houses of Clipstone, had by command expended. The same Brian was also to be settled with for what he had expended while himself held that custody, after the said Philip had been deposed. The different styles of spelling the late Custodian's name are but accountable variations of one word, well known as a surname in its modern form. The Anglo-

1215: March 26th -

King John paid his last visit to Clipstone. He was here on the 26th and 27th; the 28th he was at Kingshagh; and on the 29th he was again at Clipstone. The latter date,— evidently a mere coincidence,—was the anniversary of the first visit of King Richard twenty-

1215: March 29th -

1216: The King on the 25th February, while at Lincoln, issued writs to numerous constables, including one to the Constable of Clipstone, commanding them not to take the revenues of the lands or fees, in their respective bailiwicks, which were in the custody of William Brewer—that which had already been taken to be without delay rendered. This, if it is not another name for the Custodian or Keeper, is the only reference to such an official. It would be a decided acquisition if we could print, what a thorough search through the public records could alone supply, viz.: a list of all Chaplains, Keepers, Constables, and other officials of Clipstone, to which odd references will be found in divers places (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

Henry III

1219-

1220: 1 May 1220 “Westminster. Nottinghamshire. To the sheriff of Nottinghamshire. The king as committed to his beloved and faithful Brian de Lisle, chief justice of the king’s forests , the king’s houses of Clipstone and the same vill, to keep for as long as it pleases the king. Order to cause Brian to have full seisin without delay. Witness H. etc.” [Fine Roll C 60/15, 5 HENRY III (1220–1221). Available from: http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/content/calendar/roll_015.html] http://www.foresttown.net/index.php/heritage/clipstone-

1220: Henry, on the 23rd November, while at Winchester, directed the Barons of his Exchequer to reckon with Philip Mark, Sheriff, for seven pounds and eightpence, spent by him in reparation of the great Dam and Mill of Clipstone, and in repairing the Pale about the King's Houses there. Mr. Yeatman gives this amount, from the Sheriff's account, as £7 6s. 8d. (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1221: The King, on the 15th June, being at Blythe, directed the following writ to Brian de Insula: You are commanded to take with you a Verderer of the bailiwick of Clipstone and go to Clipstone to view the burnt houses of our poor men there; and allow the same men a reasonable allowance of building-

The above is an item of special interest. This, no doubt, is to what Thoroton refers when he says that Clipstone was burned it seems and repaired again before 5th. Henry III., 1220-

1223: the king’s chamber was damaged by fire, and Master Robert de Hotot, one of the King’s carpenters, rebuilt it by taskwork for 15 marks. (Colvin Vol II p 919).

1223: The King, while at Westminster on the 7th February, wrote commanding the Sheriff of Notts., without delay, to make reparation of the King's chamber of Clipstone,—the cost so incurred, by view and testimony of legal men, to be computed to him at the Exchequer.

At the same time and place another writ was directed to Brian de Insula, commanding him to allow the Sheriff to have, for the purpose, building-

1225: November 12th. Hugh de Nevill was commanded to allow Brian de Insula to have —apparently for the second time—full seisen, or possession, of the Lord the King's Houses of Clipstone, with the Park, Hays, &c., and their appurtenances, which the King commits to his custody during pleasure (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1227: 31 August 1227 “Concerning the manor of Clipstone. The king has committed the manor of Clipstone to the sheriff of Nottinghamshire to keep to the king’s use for as long as it pleases the king. Order to B. [Brian] de Lisle to cause the money that he received to repair the king’s chamber of the same manor and has not yet put towards the repair to be delivered to the sheriff of Nottinghamshire, whom the king has ordered to cause that chamber to be repaired.” (Fine Roll C 60/27, 12 HENRY III (1227–1228). Available from: http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/content/calendar/roll_027.html) http://www.foresttown.net/index.php/heritage/clipstone-

1233: The Kings Chamber was again rebuilt at a cost of £130

From a subsequent account it appears that it stood on an undercroft. (Colvin Vol II p 919).

1235-

1236: 7 June 1236 “Concerning the manors of Kingshaugh and Clipstone. The king has committed his manors of Kingshaugh and Clipstone and the honour of Peverel of Nottingham with appurtenances to Roger of Essex to keep for as long as etc. , so that he answers at the Exchequer for all issues of the same. Order to the same Roger to attend to keeping them diligently and faithfully, and when Roger comes to the king it will be provided for him so that he might be sustained from this.” [Fine Roll C 60/35, 20 HENRY III (1235–1236).

Available from: http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/content/calendar/roll_035.html] http://www.foresttown.net/index.php/heritage/clipstone-

1236: September 1236 “Concerning the king’s manors handed over to Warner Engayne. The king has committed to Warner Engayne the manors of Clipstone and of Kingshaugh with appurtenances, both woodlands and other things, to keep for as long as it pleases the king. Order to Roger of Essex to cause him to have full seisin of the aforesaid manors with corn, stock and all chattels found therein.” [Fine Roll C 60/35, 20 HENRY III (1235–1236). Available from: http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/content/calendar/roll_035.html] http://www.foresttown.net/index.php/heritage/clipstone-

1237-

1243-

1244-

1246-

1246-

1247: January. “Concerning keeping manors. The king has committed the manors of Darlton, Retford, Clipstone and Ragnall to Robert le Vavasur, sheriff of Nottinghamshire. Order to Warner Engayne to deliver those manors to him to keep for as long as it pleases the king, as aforesaid.” [Fine Roll C 60/44, 31 HENRY III (1246–1247). Available from: http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/content/calendar/roll_044.html] http://www.foresttown.net/index.php/heritage/clipstone-

1249: August 24th. For selling the king’s wines. It is written in the same manner to the sheriff of Nottinghamshire concerning the king’s wines at Clipstone, and to the sheriff of Leicestershire concerning the king’s wine at Croxton.” [Fine Roll C 60/46, 33 HENRY III (1248–1249). Available from: http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/content/calendar/roll_046.html] http://www.foresttown.net/index.php/heritage/clipstone-

1249-

1251: Only the men of Clipstone had rights of pasture within the park. There was no access at all to the neighbouring hays of Birkland and Bilhaugh. These together with the park, were administered directly by the king’s chief forest justice beyond the Trent, and were outside the control of the hereditary wardens of Sherwood, the Everinghams (Crook , D. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80. p36).

1252: The ‘new chapel’ and the queen’s chapel mentioned when the King had them glazed with plain glass and wainscoted. (Colvin Vol II p 919)

Passage-

1252: December 13, Worksop. “The sheriff of Nottingham is ordered to make a wardrobe for the queen’s use at Clipstone, and a privy-

1252: The same sheriff is commanded to make a certain passage [alea] at Clipstone from the entry of the king’s chamber to the gable of the hall, and another passage to the new chapel, and a chamber on the other side of the same hall, with a privy-

1252: “The sheriff of Nottingham and Derby is ordered to break without delay, the wall at the foot of the king’s bed in the king’s chamber at Clipston, and to make a certain privychamber for the king’s use, and cover it with shingles. Westminster, October 21.” (Turner Page 262 / Close Roll, 36 Henry III.) http://www.foresttown.net/index.php/heritage/clipstone-

After 1252 Henry III ordered no new works at Clipstone, but the buildings were repaired from time to time during the remaining years of his reign. (Colvin Vol II p 919)

1255-

At the same time Roger Lovetot was appointed Custodian of the same manors, during the King's pleasure (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1265-

Edward I

1279: Edward I at Clipstone (David Crook. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80)

1279-

Colvin suggests standing ruin may represent one or both of these new chambers. (Colvin Vol II p 919).

1280: Edward I at Clipstone (David Crook. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80)

Raine, the Blyth historian, records that during the first five days of August, 1280, the writs of Edward are dated either in Sherwood Forest or at Clipstone (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1282-

1284: Edward I at Clipstone (David Crook. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80)

1287: Pigs allowed pannage in the park for the payment of a fee, as they were in the hays, but the accounts of the agisters who controlled pannage give no indication from which vills they came (Crook , D. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80. p36).

1290: September 15th -

1290: September 20th -

1290: October 11th -

October Parliament at Clipstone called to rubber stamp the Kings Crusade and the date for departure was set as midsummer 1293 (Morris, M. 2000. A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain. Windmill Books. P228).

“Its accommodation must have been stretched to the limit, with he chancery and it’s clerks having to stay at nearby Warsop” (David Crook. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80. P35).

1290: The King, in the autumn of 1290, with a design of proceeding to the borders of Scotland, summoned the Parliament to meet him at Clipstone on 27th October. This was done, possibly, with the idea of thus being nearer Scotland than would have been the case had he called the Parliament together in London. Yet it does not appear that he was over anxious to press in that direction, for during the year he was never more than a day's journey further north than Clipstone.

At the beginning of September he was at Geddington and Rockingham; on the 11th he was at

Hardby, in this county, where, in the following month, his consort Queen Eleanor died. From 13th to 17th he was at Newstead Priory; on the 18th and 19th at Rufford Abbey. On the 20th he was at his own house at Clipstone, which, however, he left on the morning of the 23rd for Dronfield. He remained in Derbyshire until 7th October, when setting out again for Clipstone, he arrived on the 12th and remained.

On 13th October he issued an order for payment of 200 marks from his treasury to Lapus de Pistoria and his associates, merchants of Pistoria.

Edward also issued hence, during this regnal year, and doubtless, if we could ascertain, about the same date, an order for payment of 3,000 marks from his treasury to Lapus Bonchi and Gradus Pini, of Pistoria. A much larger sum was ordered to be paid the following year, as mentioned below, which probably was also on the occasion of the present visit, which covered the commencement of the next regnal year.

On the 14th October, writing hence, the King protests that he intends to go to the Holy Land, and accepts the tenths granted for that object.

The King issued another writ hence dated on Monday next after the feast of St. Luke the Evangelist, which feast is on 18th October.

On 23rd October he issued a writ for the payment of the annual fee of Francis Accursius.

The following note concerning a certain Elias de Hanville and his one servant, taken from the royal accounts, is interesting if only as recording the rate of wages at this period. "To the same for the wages of one man and the expenses of one horse, bringing the jewels which came out of the wardrobe, from Newcastle-

The Parliament was opened on St. Michael's Day, November; and the 251 pleas, with the petitions, then presented "before the Lord King," with the answers, cover twenty-

This— decidedly an event of the first importance in Clipstone's history, when probably a larger number of the nobility and great men of the kingdom were assembled than at any other time —the Parliament Oak was in all likelihood intended to commemorate. Whether the tree was planted in memory of the event, or what was the special connection, if any, between them, it is now impossible to say. The theory that the great national assemby was held around this tree, which careless writers continue to perpetuate, is almost too puerile to require correction.

Edward remained here until 11th November, and possibly one or two days later, but it is certain that he had left on the 14th. He was several days at Lexington, whence he removed to Marnham, and on the 20th he was again at Hardby. He was there up to the 28th, on which day the Queen breathed her last. She died of a lingering disease—a slow fever—and from this we can understand why the quietness and seclusion of Hardby should be chosen for her in preference to the presence of the King at Clipstone, where the Court and Parliament were to be held. The foregoing remarks, it should be added, refute the statement of certain of the chroniclers who aver that Edward was called from the borders of Scotland to the death-

1290-

1290: In an "Account of the receipts of the lands in Tynedale and Cumberland lately held by Alexander III. (of Scotland), with a statement of how the money has been applied," we find that, besides a large sum expended at Lexington, £25 and 160 was spent in repairs on the Houses, Dams, and Weir of the Manor of Clipstone (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1299: This year the King, an accredited messenger being sent, viz., his treasurer the Bishop of Chester, wrote to the Queen and his son inviting them to keep the solemnity of the birth of our Lord at his Manor of Clipstone, near Sherwood. The Queen replied that she preferred to spend the holiday at St. Albans. However, upon consultation, the King kept his Christmas at Windsor, with his son and all his family. This unfortunate perverseness of Her Majesty has deprived us of an item of interest in local history. However, as this has been the scene of one royal celebration of Christmas, in the next reign, we must rest content.

Edward II., who commenced to reign 8th July, 1307, appears to have been really fond of Clipstone, for he was here on numerous occasions, the first time being about ten weeks after his accession—or rather his proclamation (Stapleton, A. 1890. A History of the Lordship of King's Clipstone or Clipstone in Sherwood, Nottinghamshire).

1300: Edward I at Clipstone (David Crook. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80)

1301: reference to ‘the King’s wood of Clipstone called “le Parke” (Crook , D. 1976. Clipstone Park and Peel. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 80. p36).

Edward II